Are you looking to learn more about the Spanish faction in the game Cossacks 3? Then this is the guide for you! We break down the bonuses, unique units, and overall playstyle of Spain, and we even provide a bit of history on the nation. Get ready to find out all about the Spanish faction!

Introduction

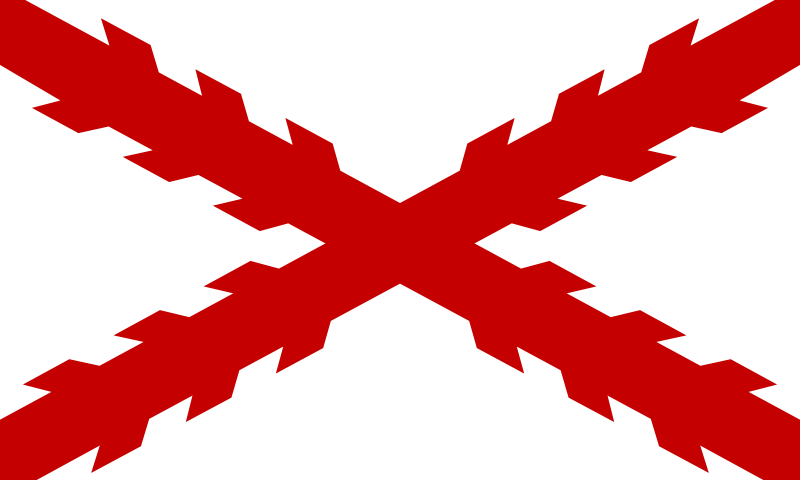

The famous Cross of Burgundy flag, featuring a red “saw-toothed” St. Andrew’s cross on a white field. Originally flown by the dukes of Burgundy, the flag was imported to Spain by the Habsburgs in 1506 and has been widely used as a symbol of the kingdom ever since.

Availability: Base game

Focus: Early/Balanced, Rush, Elite 17th century infantry

Playstyle: European

Spain is a balanced nation with an above average early game and an emphasis on its elite, armored 17th century infantry. Both the Coselete and Spanish Musketeer are one of if not the strongest unit in their respective category but are held back by their slow training times. Their presence is enough to make Spain a good pick for anyone who wants to engage in some early aggression while still having a competitive army in the 18th century.

If you like strong armored infantry, prefer quality over quantity, or just want a flexible faction that’s strong early on without sacrificing their late-game potential like some other countries, Spain is a great nation for you.

Features

+ 18c. Musketeer

+ Balloon to reveal map

~ Spanish Musketeer–individually strong but slow-training

~ Academies cost slightly slightly more wood but slightly less stone

Spain boasts the standard European tech tree, buildings, and units apart from its 17th century infantry. The only other notable difference is that Spanish Academies cost slightly more wood but less stone. This is a mixed blessing, but it’s a small enough deal that it shouldn’t affect your playstyle at all, making Spain a very easy nation to pick up and play.

A Very Brief History of Spain, 1600–1789

Coselete (17th century)

Base stats:

Full upgrades:

Cost: 35 food, 7 gold, 30 iron

Training time: 5.5 seconds

+ Strong pikeman who performs above average in both the early and late game

+ Great stats

+ High bullet armor

+ Efficient population-wise

+ Good for both early fights and tanking bullets

– Slow training time

– High iron cost

– Can be overwhelmed by more spammable melee units early on

The Coselete is the strongest pikeman of the early game on a one for one basis, improving on both the melee stats and bullet-tanking abilities of the standard 17c. Pikeman. That doesn’t make him the best pikeman for rushing (although he’s still quite good at it), but it does give him a usefulness across the entire game length that few other 17th century melee units can match.

Stat-wise, the Coselete is basically an improved 17c. Pikeman–same idea of an armored melee unit but with an extra 2 attack, 10 HP, 2 bullet armor, and better resistances against swords and arrows (though not, critically, against pikes). The tradeoff is that the Coselete takes a full second longer to train, bringing his training time up to a lengthy 5.5 seconds. In a game where quantity often beats quality, that’s a big price to pay, and it’s impressive that the Coselete does so well even with such a large handicap.

Coseletes are mostly known for their rushing potential. They decisively beat 17c. Pikemen (and Austrian Roundshiers) with equal upgrades even when outnumbered, giving Spain a strong early advantage over nations relying on those units. A small force of Coseletes and mercenaries can seriously threaten most nations in the early game while also saving wood and stone from not needing to build so many houses to accommodate their troops (the upside of a quality over quantity approach).

Putting rebels in their place: Coseletes and mercs overrun a Dutch base.

While the Coselete makes Spain a good nation for rushing, he by no means makes them the best at it. Russia, Poland, Portugal, Switzerland, Scotland, and the Islamic nations all have strong 17th century units that, though individually weaker, can easily outspam and overwhelm a force of Coseletes if the Spanish player isn’t careful. These nations are all better at rushing than Spain, and it’s best to play defensively if you find yourself starting near one of them.

Quantity beating quality: 87 Coseletes vs. 120 Portuguese Pikemen, representing the sort of army both nations can field from two Barracks after 4 minutes.

The downside of all these other strong rushing units (with the exception of Russian Spearmen and Swiss Pikemen) is that they lack bullet armor. Polish and Scottish Pikemen get shredded by massed musket fire. Light Infantry do even worse and Portuguese Pikemen only do slightly better.

The Coselete, by contrast, has no problem tanking enemy fire thanks to his 100 HP and max bullet armor of 10. Here’s a chart to illustrate what I mean:

Shots to kill (full upgrades)

Discounting headshots, Coseletes take 7 hits from generic Musketeers to kill, putting them in between the generic 17c. Pikeman’s 6 hits and the Austrian Roundshier’s 8 hits. This isn’t the entire picture, since the 17c. Pikeman trains faster and can form a tankier bullet sponge by sheer weight of numbers, but a force of Coseletes will be nearly as good while still being far more pop. efficient and a much greater melee threat.

This, then, is the Coselete’s strength compared to other unique pikemen: He’s always good, regardless of what stage the game is in. This frees up Spanish players to pursue just about any strategy as they aren’t wedded to a certain playstyle.

One last note: Coseletes look very similar to Swiss Pikemen at a glance, which can be confusing if both nations are present. To tell them apart, look at their arms and legs: Swiss Pikemen have colored sleeves and a knee-length skirt going down behind their legs, whereas Coseletes don’t.

History–“Coselete” is a Spanish term for a type of cuirass, usually made of leather. It was also used more generally to refer to soldiers who wore such protection, much like cuirassiers. In a tercio, this usually meant the pikemen as they were the most likely to be armored.

While Spanish armies included vast numbers of foreigners (as was common for the era), the cream of the army was always the natively-raised Spanish tercios. These units were recruited almost entirely from young volunteers who signed on for many years and were paid directly by the state. Service in the tercios was a popular profession for young lower-class Spaniards who would otherwise be confined to lives of drudgery at home, and even the younger sons of Iberian gentry sometimes spent a brief period in the ranks.

On campaign, Spanish soldiers were noted for their harsh discipline, unflinching courage, and poor behavior towards locals (even allied ones, with the people of Savoy finding that they preferred the presence of French invaders over “friendly” Spanish troops). For most of the 1500s they were widely viewed as the finest infantry in Europe and even during their twilight in the mid-1600s they remained capable and tenacious foes.

Pictured: A Spanish tercio awaits its destruction in the last phase of the Battle of Rocroi on May 19, 1643. While this crushing defeat by France forever shattered the tercio’s reputation of invincibility, the native Spanish infantry still conducted themselves with incredible bravery, even in the face of certain death.

Spanish Musketeer (17th century)

Base stats:

Full upgrades:

Cost: 40 food, 12 gold, 20 iron

Training time: 7.5 seconds

Range: 15.94

Rate of fire: 5.94 seconds max: 2.91 seconds min.

+ Strong armored musketeer

+ High damage

+ Above average range

+ High bullet armor

+ Affected by Blacksmith and Academy armor upgrades

– Very slow training time

– No melee attack

– Slow rate of fire

– Extra iron cost can be slightly draining on an early economy

Like the Coselete, the Spanish Musketeer is a stronger, slower-training, heavily armored version of its generic counterpart. And just like the 17c. Musketeer, they’re a situational unit that takes longer to get running than pikemen but can be very formidable in the mid game.

Stat-wise, the Spanish Musketeer improves on almost every aspect of the normal 17c. Musketeer: With full upgrades, he has +15 HP, +5 attack, slightly longer range, and a whopping 9 bullet armor. That armor combined with their increased HP makes Spanish Musketeers as good as normal 17c. Pikemen at resisting incoming fire (see the table above).

There are downsides, of course. Like all Musketeers of the 17th century, the Spanish Musketeer has no melee attack, making him vulnerable to fast-moving melee units: His reload rate is also slower (2.91 seconds vs. 2.3), though his better range and attack mostly make up for that. Worst of all, however, is his painfully long 7.5 second training time. This is the unit’s achilles’ heel and it holds the unit back from being any better than above average.

A 15-minute peacetime Spanish army makes mincemeat out of a poorly conceived Portuguese force. (AI army composition seems to assume no peacetime, hence the pikes.)

Spanish Musketeers perform well in the same situations as other 17th century Musketeers, namely games with peacetimes of 15 minutes or more. They’re not as good as Polish or Dutch Musketeers (to say nothing of Serdiuks, Strelets, and Janissaries) but they’ll comfortably outperform Austrian, Scottish, and normal 17c. Musketeers. Their higher attack means they punch through the armor with ease while simultaneously giving you more population space for other units. Even Hungarian Hajduks can struggle against fully upgraded Spanish Musketeers since the Spaniards’ 30-damage attack will two-shot them.

Aside from looking cooler, though, Spanish Musketeers don’t radically change Spain’s tactical or strategic options. They’re still better performing, more population efficient versions of the 17c. Musketeer, but they’re no more than that.

History–During the tercio’s heyday in the 16th and early 17th centuries, the pikemen were the core of the formation while the musketeers played a supporting role. In battle, each pike block was to be accompanied by so-called “sleeves” of musketeers on either side of it. It was the musketeers’ job to screen the pikemen’s advance and disrupt the enemy before the two sides met in melee. In return, the pikemen provided protection for the musketeers, who could seek shelter in the main body when threatened by cavalry or other infantry. It was a flexible, fluid system and a critical step forward in infantry tactics and organization.

Nothing remains good indefinitely, however, and over time thoughtful observers began to notice the tercio’s flaws. One of the most important critiques leveled at the formation was that it failed to utilize the full potential of its musketeers. In a classical tercio, the musketeers did not coordinate their shooting; each man was free to aim, fire, and reload at his own pace. While this increased individual accuracy, it also meant that the morale impact on opposing soldiers was rather minimal, which paradoxically hindered the musketeers’ effectiveness and limited them to a mere harassing role. Contemporary commentators also criticized the depth of the tercio’s sleeves since only a fraction of the musketeers could fire at any given time, wasting a lot of potential firepower. (The cavalry tactic of the caracole drew similar complaints.)

These flaws in the tercio, plus improvements in firearm technology, led various military thinkers across Europe to try and come up with ways to use their musketeers more effectively. Infantry formations gradually became less dense and more linear with a higher ratio of muskets to pikes as rank-firing and volley fire methods elevated the importance and effectiveness of firepower. Whereas the constant, scattered gunfire of the early tercios required a long time to break an opposing formation, the thunderous volley of hundreds of muskets firing simultaneously at close range often had an immediate and shattering effect on enemy morale, especially if followed up by a charge. Thus the musketeer replaced the pikeman as the decisive arm of infantry combat.

The Spanish, for their part, were not blind to these new developments and continually modified the tercio to incorporate their enemies’ methods. By the late 1600s, Spain’s tercios were mostly made up of musketeers fighting in linear formations with only small groups of pikemen for support, a trend that would only increase once bayonets eliminated the need for dedicated melee infantry.

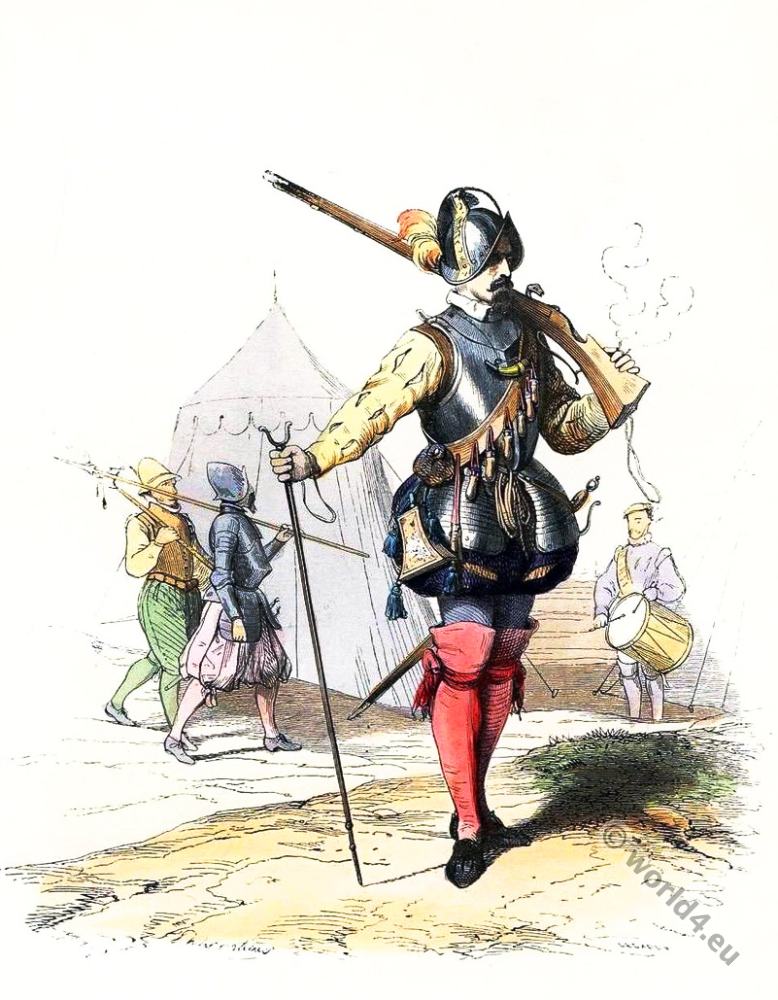

Pictured: An armored musketeer from the late 1500s. While most musketeers of the 17th century went into battle with little to no protection, a few lucky ones could afford better armor like the one pictured. The in-game Spanish (and Austrian) Musketeers are based on these few fortunates.

Gameplay

NOTE: This section assumes you’re playing without capture rules and are thus limited to Spanish units and buildings. While capturing can be fun, it also dilutes the factions’ unique characteristics and forces a much more turtling-centric playstyle, which is why many online matches don’t use it.

Early game (early 17th century)

Spain has an above average early game, especially in games with little or no peacetime where you can leverage its high-quality 17th century infantry to your advantage. You’ll need to be wary of stronger rushing nations, such as Poland and the Islamics, but against all others you should enjoy a healthy margin of superiority. Take advantage of this to bully your enemies and kill or cripple their bases if you can.

Aside from that, Spain plays pretty much the same as other European nations and uses the standard openings. In 0 peacetime games you’ll be fielding Coseletes to make use of their early-game prowess. If the peacetime is 15 minutes or more, use Spain’s elite Musketeers.

The armored pain train won’t stop: Coseletes and mercenaries rush the second base of the game. (The AI isn’t good at supporting each other; this would be much harder against skilled players.)

Mid game (late 17th/early 18th century)

Here Spain is, once again, above average. In games with 15+ minute peacetimes your unique Musketeers will give you, if not a decisive edge, at least a small leg up over most other nations. If it’s a larger game and you have a choice of targets, prioritize the nations with a stronger late game than you, such as Bavaria or Prussia. Taking them out before they get too powerful will greatly improve your odds if the game goes late.

Your army at this point should be composed of your infantry of choice (dependent on how long the peacetime was) plus mercenaries, your first artillery, and whichever cavalry you prefer. Pairing Coseletes with Dragoons or Musketeers with melee cavalry will ensure your army has plenty of firepower while still maintaining a strong bullet screen. Do be careful about bunching your slow-training infantry up lest a few well-aimed cannonballs delete a significant chunk of your army.

Red ball of death: A late-game Spanish army forces its way into the enemy’s town. (Good thing there aren’t many cannons around because damn my troops are bunched up!)

Late game (late 18th century)

By this point most nations are fielding powerful gunpowder armies. Spain’s performance is pretty average at this stage. Average in Cossacks is still good, however, and it’s significantly better than most stronger rushing nations have it in the late game. Now’s the time to turn the tables on factions like Poland and Scotland who were threatening you earlier and see how they like being bullied.

Your army in this period will be composed of the typical mix of 18c. Musketeers plus artillery, your choice of cavalry, and whichever 17th century infantry you picked earlier. The Coselete excels as a bullet sponge since Spain doesn’t need as many of them to form a strong screen for its army, allowing room for more 18c. Musketeers and cavalry. The Spanish Musketeer is a bit trickier to make work but they’re nearly as tanky as the Coselete and put out far more damage, though their lack of a melee attack could be problematic if melee troops reach them.

Example Games

COMING SOON!

Closing Remarks

The current flag of Spain, which proudly displays the kingdom’s coat of arms. The flag’s design dates back to 1785 (right at the end of the game’s timeframe) and, much like the Spanish people themselves, it has survived all manner of troubles over the last two and a half centuries including invasion, civil war, and fascism.

So that’s Spain! A good early nation that remains strong through the late game.

I hope you enjoyed my guide! I’m planning to do more of these going forward. Next up will probably be Prussia or maybe Piedmont. Let me know you thoughts and if you have any suggestions about Spain or which nation should get the next guide!

Other Cossacks 3 nation guides:

Portugal

And that wraps up our share on Cossacks 3 Faction Guide: Spain. If you have any additional insights or tips to contribute, don’t hesitate to drop a comment below. For a more in-depth read, you can refer to the original article here by PirateMike, who deserves all the credit. Happy gaming!